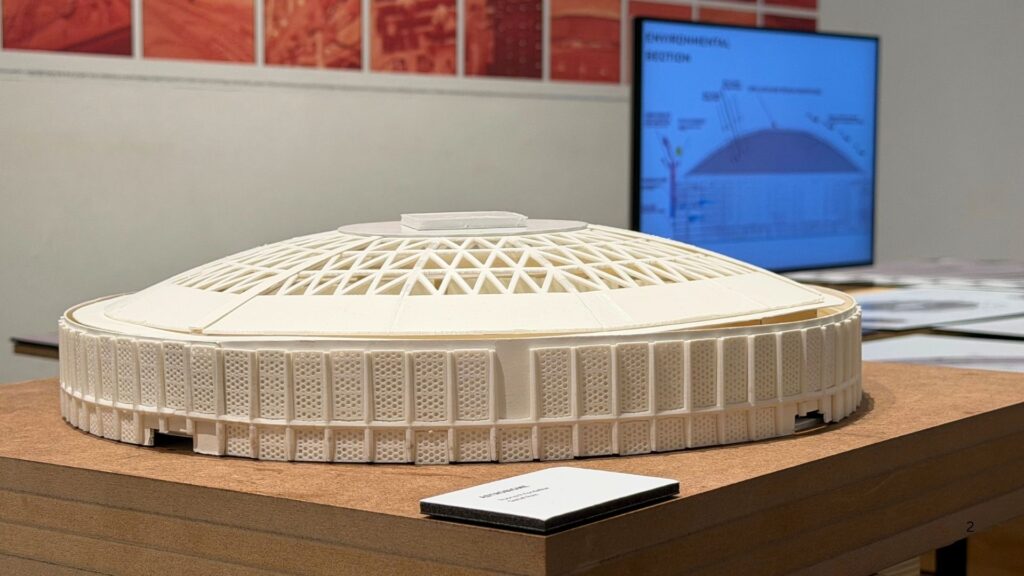

Standing in the University of Houston’s Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture, surrounded by meticulously crafted 3D models and glowing digital renderings, I realized I was looking at a version of Houston that feels both hauntingly familiar and radically new. The Astrodome, hailed in 1965 as the “Eighth Wonder of the World,” for being the first of its kind, stands today as a relic of mid-century modernity after years of stagnancy from Harris County, who owns the revolutionary building. For years, it has been an engineering marvel frozen in obsolescence, caught in a political tug of war between the cost renovation and the perception of a wrecking ball.

But for the senior architecture students at UH, the Dome isn’t a political headache. It’s a testing ground. Through the Fall 2025 semester, nineteen students participated in DOMEafterDOME, a capstone project presented by The BASE Lab (Building Analytics and Sustainable Environments Laboratory) and supported by Amazon. They were asked to rethink obsolescence as an opportunity for innovation, reimagining this million square foot landmark as a sustainable, functional piece of the 21st century Houston.

A Generational Divide and a New Perspective

What struck me most as I walked through the exhibition was a startling fact: 100% of the students who worked on this project have never actually been inside the Astrodome. For them, there is no muscle memory of a Nolan Ryan no-hitter, a Jeff Bagwell home run, an Earl Campbell touchdown during the Luv Ya Blue era, or the roar of the crowd a rodeo.

Assistant Professor Mili Kyropoulou, who led the studio, noted that this generational divide actually became their greatest asset.

“It has been vacant for so long that people that are now the age of the students inevitably have not experienced the building,” Kyropoulou told me. “At the beginning, that was very interesting… where students very often were caught in surprise with different facts that people like yourself, or myself that have studied the building before, were so familiar with, in a way that we think everybody knows about.”

She says her students became hooked and inspired by what they were discovering. Because they lacked personal history with the structure, they could look at the engineering, from its innovative knuckle columns and the steel Lamella truss roof, with fresh eyes.

“They approached it in a completely unbiased way where they were not emotionally attached in one or the other direction,” Kyropoulou said. “And they could as, if you want, like yourself, like a journalist, going to another city, you have never been… they come in as architects in training to study the building, which is a fabulous case study, and explore those endless possibilities without any bias.”

Designing for Houston’s Future

The students didn’t just dream; they analyzed. Using specialized simulation tools, they tackled the “concrete sea” surrounding the building and the potential for the structure to become climate responsive. Maria Christofi, the studio’s co-instructor, pushed the students to think about how mega structures like the Astrodome impact Houston.

“Those kind of structures are not just buildings that need to be renovated and reused. We are bringing a lot of variables, and also many contributors that need to deal with this project, to bring it back to life,” Christofi explained.

Christofi, who has spent the last decade on the East Coast, shared that same sense of wonder as if she were originally from Houston. Even as an instructor, she felt the pressure of the building’s perceived looming deadline.

“I didn’t have the privilege to enter the Astrodome, but I’m living close by it now. I know how mega structures like the Astrodome are important to the urban tissue,” she said. Her enthusiasm for the Astrodome is contagious, a quality that resonated with students. “If you teach something, you have to be passionate about it. It seems we only have a limited time to bring it (the Astrodome) to life.”

The “First Step on the Moon”

Among the nineteen students was Brandon Chau. Despite never stepping foot inside the structure, Brandon’s approach was deeply human. He spent his semester interviewing those who did remember the Dome’s glory days to understand how a building could define a city’s identity.

“For me, the process began really looking from a history side, where I wasn’t born,” Chau said. “I actually started interviewing people who’ve been inside the Astrodome and learning about their experience… how that was such a cultural moment for them and how they made how it made them feel like they’re in Houston. This was the building that made Houston, Houston.”

Brandon compared the Dome’s 1965 opening to a global milestone. “The Astrodome, being the first indoor stadium, became the catalyst of the cascading sports facilities that came after it. I think having that first step, it’s like the first step on the moon, a memory that people will cherish as a milestone in history.”

As we looked at his project, which focuses on the shared space and technological advancement the Dome represents, Brandon reflected on his own transformation through the work. He told me, “I felt like I got a little closer to the city and understand what really makes Houston.”

The Next Chapter

While the Astrodome is protected as a Texas State Antiquities Landmark (like the State Capitol and Alamo), its daily reality remains one of stagnation. Harris County still holds the decision making power, and the public is often left with daunting renovation or demolition figures. In December, Harris County released a figure of $753 million to renovate versus $55 million to demolish. The report did not make any recommendations but Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo says renovation costs are not in the budget and would require significant private money. The Astrodome Conservancy has championed a public-private partnership for years and says they have been in discussions with “multiple private large-scale developers.” Meanwhile, the Houston Texans and Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo have dismissed the conservancy’s plans as they work on long-term stadium sustainability at the county-owned NRG Park, where the Astrodome sits in the middle of.

DOMEafterDOME offers a different narrative. It shows the building as a “climate responsive and human centric” space. Each project developed a primary program, ranging from Data Infrastructure and Food Ecosystems to Logistics and Media Production.

Kyropoulou emphasized that these aren’t just pretty pictures; they are the result of rigorous research. “Every step they took, they were trying to have it be the result of an analysis process,” she said. “And analysis process that, again, started from the urban level… to the building level, and the potential it may have. For example, to have PV (Photovoltaic) panels on the roof, or completely open the roof and create an open air project.”

The exhibition is a reminder that the Astrodome can still be a site of public imagination and should be used for the public. It doesn’t have to be a static relic. For the faculty and students, even without ever setting a foot inside, there is a sense of pride that Houston is home of the Astrodome.

If You Go

The DOMEafterDOME exhibition is a must-see for anyone invested in the future of our city. It is on display through February 4, 2026, at the Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture.

- Closing Lecture: February 2nd in the Mashburn Gallery.

- Topic: A deep dive into adaptive reuse and the future of the Astrodome.

- Online: Explore the full proposals and videos at domeafterdome.com.